Ear infections are practically a rite of passage into adolescence, as most children experience this ubiquitous childhood malady at least once—often several times—as they mature. Furthermore, as most parents are aware, trying to get young children to take medication orally can be trying at the best of times, let alone several times a day while they are experiencing pain in their head. Now, a team of scientists at Boston Children's Hospital in collaboration with investigators at Boston Medical Center and Massachusetts Eye and Ear has just published data from a preclinical study that could make treatment of this common childhood illness potentially safer and much easier for both the patient and the parents.

“Force-feeding antibiotics to a toddler by mouth is like a full-contact martial art,” quipped lead study investigator Daniel Kohane, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children’s Hospital. Dr. Kohane and his colleagues found that a single application bioengineered gel, squirted in the ear canal, could deliver a full course of antibiotic therapy for middle-ear infections

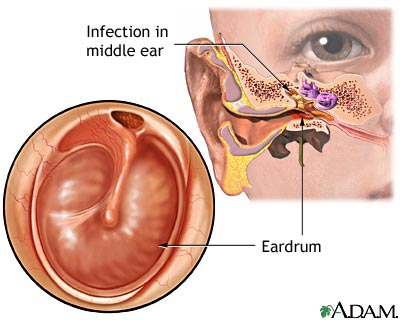

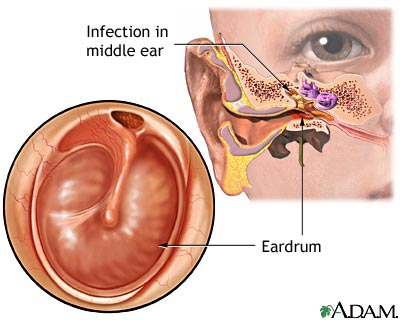

Middle-ear infection, or otitis media, affects 95% of children, prompting 12 to 16 million clinical visits per year in the U.S. alone. It's the number one reason for pediatric antibiotic prescriptions. Unfortunately, because children often seem to improve within a few days, parents often stop treatment too soon. Incomplete treatment and frequent recurrence of otitis media (40% of children have four or more episodes) encourages the development of drug-resistant infections. And because high doses are needed to get enough antibiotic to the ear, side effects like diarrhea, rashes, and oral thrush are common.

"With oral antibiotics, you have to treat the entire body repeatedly just to get to the middle ear," remarked lead study investigator Rong Yang, Ph.D., a chemical engineer in Dr. Kohane's laboratory. "With the gel, a pediatrician could administer the entire antibiotic course all at once, and only where it's needed."

The research team developed a new antibiotic gel that when squirted into the ear canal, quickly hardens and stays in place, gradually dispensing antibiotics across the eardrum into the middle ear. "Our technology gets things across the eardrum that don't usually get across—in sufficient quantity to be therapeutic," noted Dr. Kohane.

The findings from this study were published recently in Science Translational Medicine in an article entitled “Treatment of Otitis Media by Transtympanic Delivery of Antibiotics.”

The eardrum clinically referred to as the tympanic membrane, has long been viewed as an impenetrable barrier. The newly bioengineered gel gets drugs past it with the help of chemical permeation enhancers (CPEs), compounds FDA-approved for other uses that are structurally similar to the lipids in the stratum corneum, the eardrum's outermost layer. The CPEs insert themselves into the membrane, opening up molecular pores that allow the antibiotics to seep through.

Amazingly, the researchers did not observe any toxicity from their method and the antibiotic was undetectable in the animals' blood. While the investigators initially noted a slight hearing loss in some animals—similar to that caused by earwax— they found that giving less of the gel alleviated the problem.

"Transtympanic delivery of antibiotics to the middle ear has the potential to enable children to benefit from the rapid antibacterial activity of antimicrobial agents without systemic exposure and could reduce the emergence of resistant microbes," concluded study co-author Stephen Pelton, M.D., a pediatric infectious disease physician at Boston Medical Center.

“Force-feeding antibiotics to a toddler by mouth is like a full-contact martial art,” quipped lead study investigator Daniel Kohane, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children’s Hospital. Dr. Kohane and his colleagues found that a single application bioengineered gel, squirted in the ear canal, could deliver a full course of antibiotic therapy for middle-ear infections

Middle-ear infection, or otitis media, affects 95% of children, prompting 12 to 16 million clinical visits per year in the U.S. alone. It's the number one reason for pediatric antibiotic prescriptions. Unfortunately, because children often seem to improve within a few days, parents often stop treatment too soon. Incomplete treatment and frequent recurrence of otitis media (40% of children have four or more episodes) encourages the development of drug-resistant infections. And because high doses are needed to get enough antibiotic to the ear, side effects like diarrhea, rashes, and oral thrush are common.

"With oral antibiotics, you have to treat the entire body repeatedly just to get to the middle ear," remarked lead study investigator Rong Yang, Ph.D., a chemical engineer in Dr. Kohane's laboratory. "With the gel, a pediatrician could administer the entire antibiotic course all at once, and only where it's needed."

The research team developed a new antibiotic gel that when squirted into the ear canal, quickly hardens and stays in place, gradually dispensing antibiotics across the eardrum into the middle ear. "Our technology gets things across the eardrum that don't usually get across—in sufficient quantity to be therapeutic," noted Dr. Kohane.

The findings from this study were published recently in Science Translational Medicine in an article entitled “Treatment of Otitis Media by Transtympanic Delivery of Antibiotics.”

The eardrum clinically referred to as the tympanic membrane, has long been viewed as an impenetrable barrier. The newly bioengineered gel gets drugs past it with the help of chemical permeation enhancers (CPEs), compounds FDA-approved for other uses that are structurally similar to the lipids in the stratum corneum, the eardrum's outermost layer. The CPEs insert themselves into the membrane, opening up molecular pores that allow the antibiotics to seep through.

Amazingly, the researchers did not observe any toxicity from their method and the antibiotic was undetectable in the animals' blood. While the investigators initially noted a slight hearing loss in some animals—similar to that caused by earwax— they found that giving less of the gel alleviated the problem.

"Transtympanic delivery of antibiotics to the middle ear has the potential to enable children to benefit from the rapid antibacterial activity of antimicrobial agents without systemic exposure and could reduce the emergence of resistant microbes," concluded study co-author Stephen Pelton, M.D., a pediatric infectious disease physician at Boston Medical Center.